The baseball legend won over a divided city and country with his talent, not his talk

In November 1957, two months after the New York Giants struck a deal to move the franchise to San Francisco, Willie Mays placed an offer on a brand-new home. This house was on Miraloma Drive, in a placid section of the city adjacent to the upscale planned community of St. Francis Wood. A span of glass windows offered a sweeping view of the Pacific Ocean. Mays and his wife, Marghuerite, made an all-cash offer. And Walter Gnesdiloff, the contractor who built the house, refused to take it.

Gnesdiloff claimed that his hands were tied. He said that his business would suffer if he sold this house to a Black man. That the neighbors and the so-called “neighborhood improvement clubs” had already besieged him with telephone calls. One neighbor said publicly that he “stand[s] to lose a lot if colored people move in.”

Mayor George Christopher’s aides found them another home in a neighborhood that a local social justice advocate said had “become heavily Negro in ownership.” Mays and Marghuerite insisted on sticking with their offer on the Miraloma home. Christopher, sensing a looming public relations disaster and trying to placate both sides, stepped in and convinced Gnesdiloff to sell his house to Mays for $37,500, which was $5,000 more than the price at which it had previously been offered to a white potential buyer.

A year later, Mays and his wife did an interview with local television station KPIX. There had been rumors in the newspaper about marital strife; at one point, the interviewer asks Marghuerite whether it’s true that “you’re not as happy in San Francisco as we’re happy to have you.” Marghuerite plays along—she blames the rumors about them on one man who holds a grudge—but the pain is apparent on her face. San Francisco, at that moment, was largely segregated and provincial, grounded in the kind of working-class white conservatism that swept Christopher—a Republican who owned a dairy that refused to employ Black people—into two terms in office. The city liked to see itself as cosmopolitan and enlightened and cultured, but Mays had held up a mirror to it without ever saying anything overtly political at all.

Said the San Francisco chapter of the NAACP: “What happened in Mays’s case is dramatically enacted daily by hapless Negro families whose lack of prominence does not command the attention of the press and officials of San Francisco.”

Said one ABC commentator: “It seems some of the citizens of San Francisco, often called the country’s most sophisticated city, dwell behind picture windows which do not conceal their prejudices.”

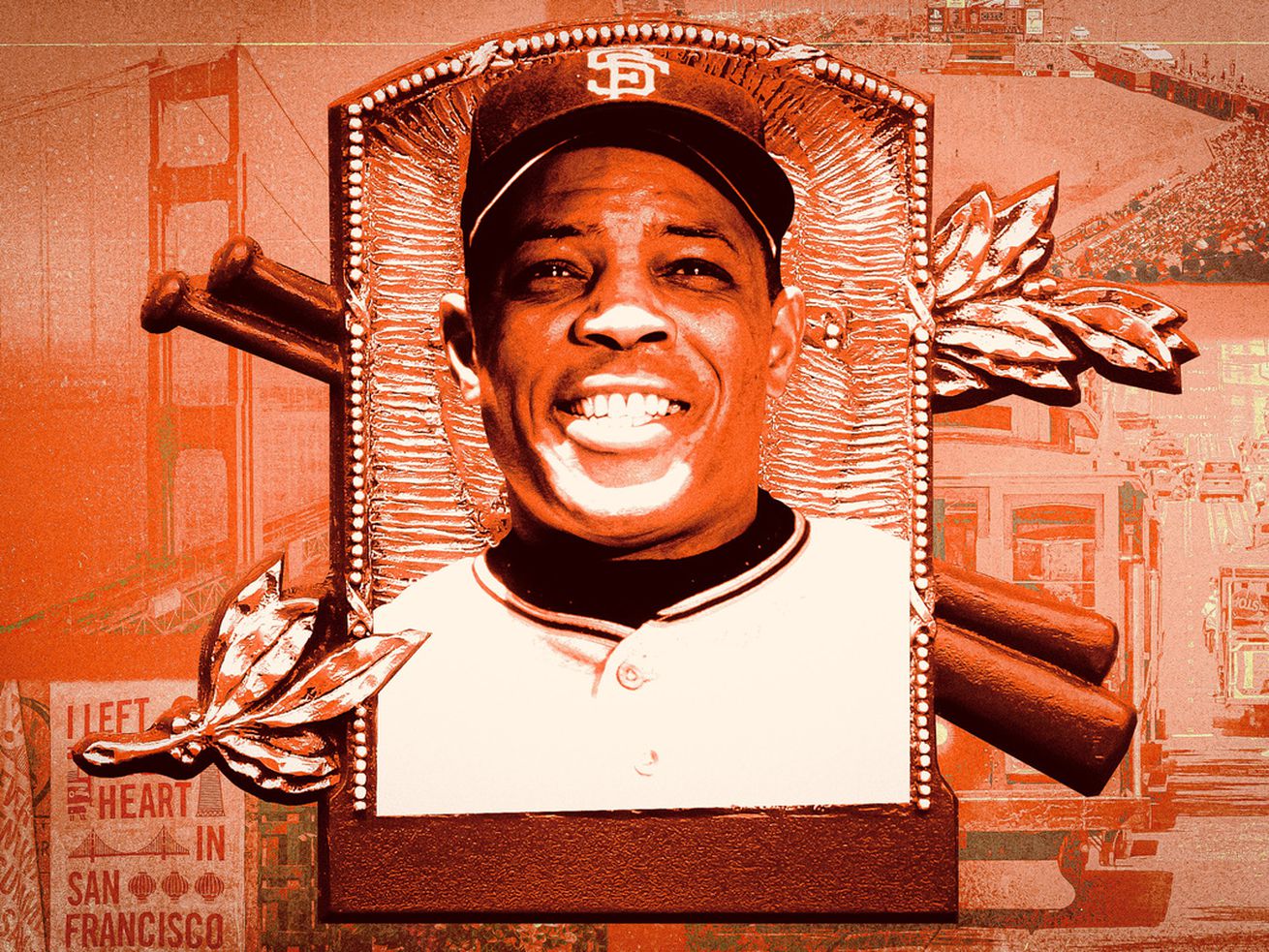

Willie Mays, who died at the age of 93 on Tuesday, came of age in the Deep South. He became a superstar in broad-shouldered New York City, amid a golden era of center fielders—Mays, Mickey Mantle, Duke Snider—on three different baseball clubs. But in San Francisco, he became an icon, at the very moment when a city endowed with natural beauty was forced to reckon with its inner self. Merely by being there, by standing above it all, Mays helped to move the city, to force people to reckon with what was happening behind those picture windows. And by changing San Francisco, Willie Mays helped change America as we know it.

Three months before Willie Mays bought that house, at the same time that the Giants were finalizing their move to San Francisco, the author and City Lights bookstore owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti sat in a municipal courtroom, on trial for obscenity for publishing and selling copies of Allen Ginsberg’s epic poem “Howl.”

The judge ruled in favor of Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg. And the city—increasingly populated by a generation of young newcomers, by soldiers who had seen its beauty in the midst of World War II and decided to stay, by Black people and immigrants seeking good jobs, by hipsters and beatniks who were no longer satisfied with the placid status quo—became a cultural fulcrum. San Francisco would never again elect a Republican mayor after George Christopher; the city became “a beacon for people who wanted something different,” wrote KQED reporter Scott Shafer. It was no longer a sleepy, provincial town; it was a place where Black musicians thrived in the Fillmore District and where comedians and drag queens pushed the boundaries in North Beach.

Just as the provincial forces of San Francisco distrusted these newcomers with their seemingly radical ideals, they also distrusted Mays at first. They already had a hero in Joe DiMaggio, the quiet and dignified New York Yankee who had come of age not far from where Ferlinghetti placed his bookstore. Mays brought a new kind of style with him to San Francisco, and that style dovetailed with the newcomers. He wore his hat too loose so it would fly off when he ran. He was daring and graceful and powerful and beautiful.

Occasionally, in those early years in San Francisco, the fans would boo Mays, often for doing something overly bold. In early 1959, when the Dodgers tried to walk him intentionally, he reached out and swung at the fourth pitch, popping it up to the catcher. One newspaper called it “the boner of the year,” according to Mays’s biographer, James S. Hirsch. In June of that year, someone stuffed a racist note into a Coke bottle and hurled it through the picture window of his house on Miraloma Drive.

All this began to change in 1962, after the Giants defeated the Dodgers to win the pennant. “Mays considered himself, for the first time, a San Franciscan,” Hirsch wrote. The next year, Mays agreed to give access to a young filmmaker named Lee Mendelson, whose one-hour documentary on him, A Man Named Mays, features a scene of a cross section of San Franciscans all listening to a Mays at-bat on the radio: a white woman getting her hair done, construction workers on break, men at a bar, teenagers lounging at the beach, a young child being bathed in a kitchen sink, restaurant workers laboring in a cramped Chinatown kitchen. The documentary aired on NBC in 1963, three weeks after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the city where Mays had once played baseball.

“What could I have done at that particular time to stop all that?” Mays later said of the turmoil in his home state of Alabama during the Civil Rights Movement. “I’m not a politician. Even if I had gone down there, what was I going to do?”

Even so, wrote Hirsch, “The documentary on Mays … delivered a powerful message. … Mays emerged as an inspiring figure of hope and unity.”

Around the same time, a protest movement would be born across the Bay in Berkeley. And then came the 1960s, and the Summer of Love, and the Haight, and the Human Be-In. Through it all, there was Willie Mays roaming center field at Candlestick Park, the one unifying force in a city increasingly riven by generational conflict, a city that was—and still is—both beloved and despised for the way it changed the country.

Tuesday night, as word of Mays’s death circulated, people began to gather and lay flowers at the statue on the corner of Third and King streets that’s become the city’s de facto pregame gathering spot: Mays in full backswing, his gaze cast out over the city that so desperately needed him at that moment of seismic change.

Who knows what San Francisco would be, or what this country would be, without Mays’s steadying presence amid that tumultuous era? Former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, arguably the most influential politician in the city’s history, said that he was able to buy a house as a Black man only because Mays insisted on buying that house on Miraloma Drive. Barack Obama once made the case that he might have never become the first Black president if not for the way Mays charmed the country half a century earlier. On Thursday, the Giants will play a game at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, where Mays once played as a young man; it will serve as a tribute to the cultural gaps Mays managed to bridge merely by being himself.

“(He) didn’t try to change the world with utterances,” Brown told the San Francisco Chronicle. “But he did it with his demonstrated talents.”

In his 1972 poem “Baseball Canto,” Ferlinghetti—a revered icon of the San Francisco counterculture, who died in 2021—would write of how Mays kept “running through the Anglo-Saxon epic.” It was a nod to Mays’s ability to keep on moving with grace and dignity, no matter what stood in his way. And it was, perhaps, a subtle acknowledgment that one man could not have changed America without the help of another.

Michael Weinreb is a freelance writer and the author of four books.