Studios are relying on franchises to bolster their bottom lines. But eventually, that strategy has diminishing returns.

Is the box office busted, or back? It depends on which week you ask. As the movie theater industry reels from the double body blows of the COVID-19 pandemic and last year’s writers and actors strikes, forecasts for the future of cinema fluctuate wildly with each weekend’s gross. Amid movie pundits’ breathless swings between panic and relief, though, there is one constant: Whichever way the wind is blowing at the box office, it’s bound to be propelled by the performance of franchises.

In the spring and summer of sequels, the industry outlook has followed film franchises’ lead. When Inside Out 2 or Dune: Part Two dominates, the state of the multiplex seems strong. When Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire or Furiosa flops, box office obits abound. It’s silly to be swayed one way or another by a breakout hit or a prominent underperformer, but on balance, negative news has made most of the headlines this year. Overall, domestic box office earnings are down more than 37 percent compared to the same point in 2019. More concerning still, this year’s domestic receipts have slipped more than 20 percent relative to last year, following year-over-year upticks in 2022 and 2023. Causes of decline include decreased inventory due to strike-related production delays; shrinking exclusive theatrical windows; a reduction in trailer visibility, thanks to assigned seating; and increased competition from other forms of entertainment, which sparked a gradual, long-term diminishment of moviegoing (and other in-person activities) well before the pandemic accelerated the trend.

Some movie analysts argue—and some CEOs and studio execs acknowledge—that franchises themselves have driven audiences away. Franchise fatigue feels real, but the box office tailspin predates Hollywood’s all-in approach to franchise building, which suggests that the industry’s reliance on known quantities may be more of a response to precarious conditions than the primary driver of them. Regardless, it doesn’t seem likely to change: Hollywood has a fever, and for better or worse, the only prescription is more sequels. The industry’s hopes for the second half of this year hinge on making more of the same: Deadpool & Wolverine, Joker: Folie à Deux, Sonic the Hedgehog 3, Venom: The Last Dance, Twisters, Moana 2, Mufasa: The Lion King, Gladiator II, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, and so on.

Of course, non-franchise films are sometimes seen as bellwethers, too; box office observers are quite capable of claiming to perceive the secret to success in Anyone but You or freaking out about bad numbers for The Fall Guy. But it’s only logical to focus on franchises when they’re so ascendant. In 2000, only one of the top 10 movies at the domestic box office belonged to an existing film franchise (Mission: Impossible II). In 2022, the entire top 11 did. This year, the top seven earners so far are franchise films, and A Quiet Place: Day One, Despicable Me 4, Twisters, and Deadpool & Wolverine (which could take in a billion bucks despite its R rating) may make it another clean sweep of the top 11 by the end of this month.

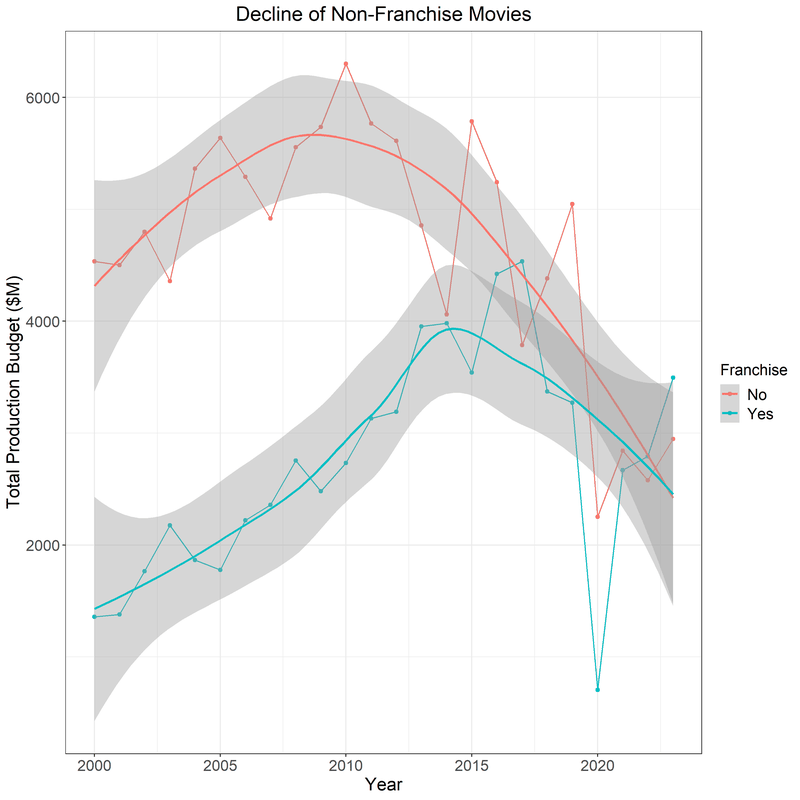

The changing composition of the box office leaderboards reflects the reality for the industry as a whole. The chart below, based on budget information from The Numbers and franchise classifications from Rating Graph, shows that as overall spending on moviemaking has trended down in recent years—and also shifted to the streaming realm, where budgets are extra opaque—franchise films make up a much larger piece of the pie. The combined budgets for s year’s franchise films, which often tend to be effects-heavy blockbusters, now roughly match—and have sometimes surpassed—the combined budgets for all of a year’s non-franchise films.

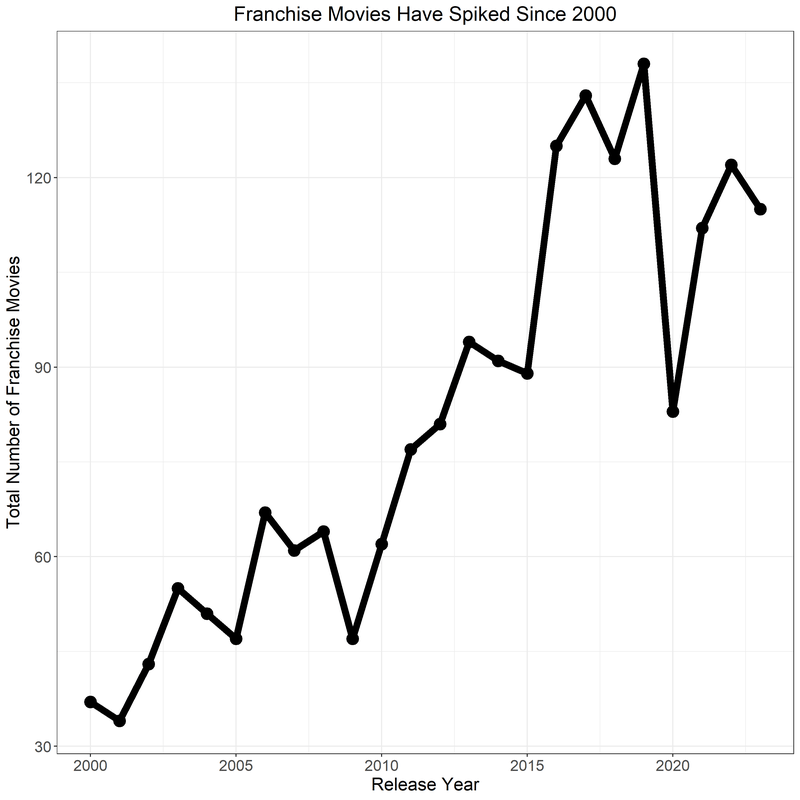

Another way to convey the industry’s pivot to franchises is through the sheer number of franchise films released each year, which has roughly tripled over the past 20 years.

One by-product of Hollywood’s increased reliance on franchises is that more film franchises are growing really long. Recent robust earner A Quiet Place: Day One is merely the third entry in the Quietverse, but Hollywood is no longer content to cap most franchises at “trilogy.” (Case in point: There’s another Quiet Place sequel on the way—plus, perhaps, a sequel to the prequel.) Even during a relative lull in big-screen releases for prolific franchises such as James Bond, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Trek, and Star Wars, fourth films and beyond have become commonplace.

Kung Fu Panda 4 and Bad Boys: Ride or Die are the fourth films in their franchises, and Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes is the fourth film in the Apes reboot timeline alone. On Wednesday, two more fourth films debuted in theaters and on Netflix: Despicable Me 4 and Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F, respectively. Furiosa is the fifth film in the Mad Max franchise, Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire is the fifth Monsterverse movie (not to mention the umpteenth King Kong and Godzilla sequel), and Frozen Empire is the fifth film in the original Ghostbusters continuity and the sixth for the franchise overall.

Even if franchise films, on average, have higher revenue floors and ceilings than original, unknown quantities—along with, often, bigger budgets—there could be a cost to repeatedly running back the same old properties, often with the same old actors attached. It would be one thing if Hollywood were continually minting fresh franchises, but trying to wring new life from so many warmed-over ones risks becoming a “blood from a stone” situation—and not just when we’re dealing with Rambo: Last Blood or sequels to Romancing the Stone. Is there a point to diminishing franchise returns? When do film franchises peak, and what does their typical aging curve look like?

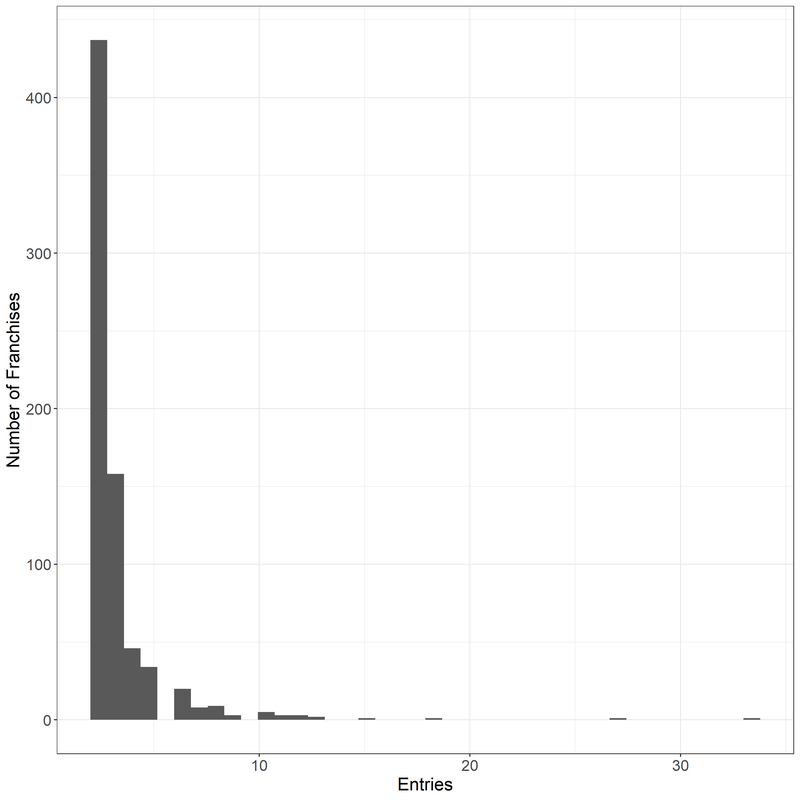

Most film franchises aren’t all that prolific. Historically, the vast majority (about 80 percent) have maxed out at two or three films, with only a few encompassing more than 10 entries:

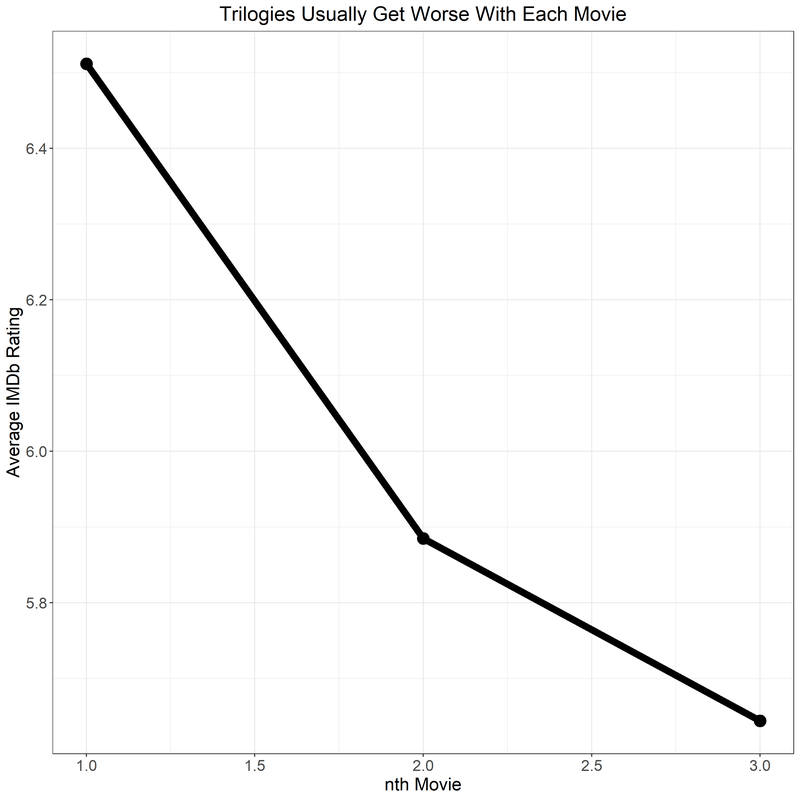

If we limit our inquiry to franchises with three installments, we find that their average IMDb user rating decreases with each release.

Now, there’s something of a selection bias at work here. Some three-part franchises are only ever intended to be trilogies; no matter the quality trajectory they take, they wouldn’t go longer than that. Others, however—like A Quiet Place—have the potential to continue beyond a third film, so by constraining our sample only to three-part franchises, we’re excluding some series that kept up their quality and thus got to keep going.

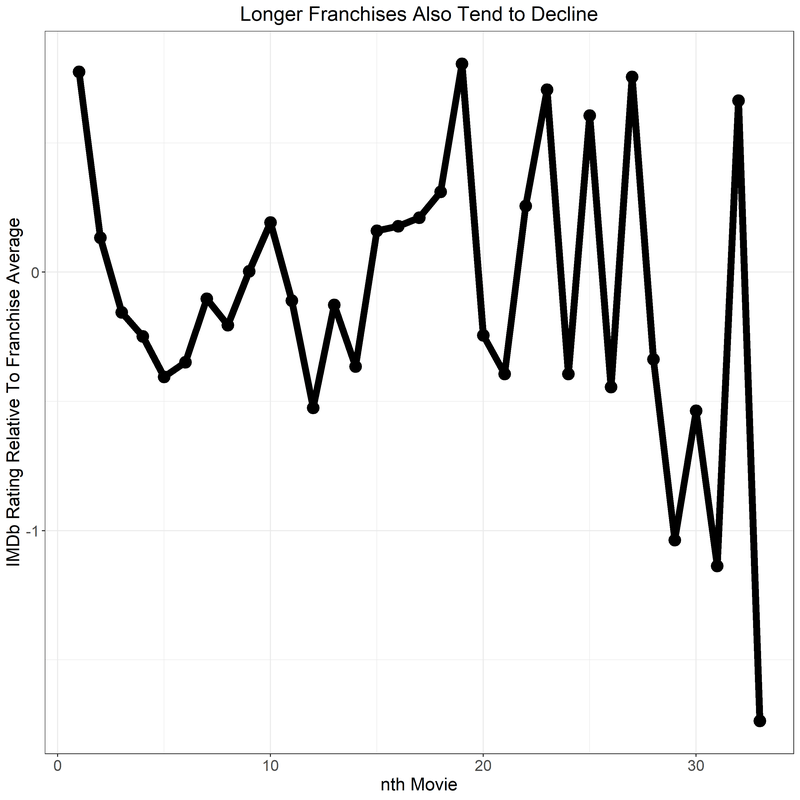

To reduce that source of bias, then, let’s open up the pool to franchises of all lengths and look at how their IMDb ratings shift over time, relative to the franchise average:

Per Rating Graph’s groupings, only 18 franchises boast a double-digit number of entries, and only six have extended beyond a dozen (though in some cases Rating Graph counts movies as members of multiple franchises, e.g., Marvel’s Avengers movies, which belong to both the MCU and the Avengers franchises). Thus, the samples shrink and the results grow more variable as the movie count climbs. It’s clear, though, that on average, it’s all downhill from the first film. The audience reception tends to bottom out around the fifth or sixth entry, as the, um, frosty reception to the most recent installment of Ghostbusters showed.

That said, studios don’t make movies to earn high IMDb audience ratings; they make movies to make money. Let’s drill down to the bottom line.

To study how the box office potential of franchises holds up over time, we have to account for inflation. Market conditions matter, too: Certain international movie markets have made bigger contributions to global grosses in some years than in others, and adjusting for inflation alone wouldn’t do much to make sense of 2020, when box offices shut down for much of the year.

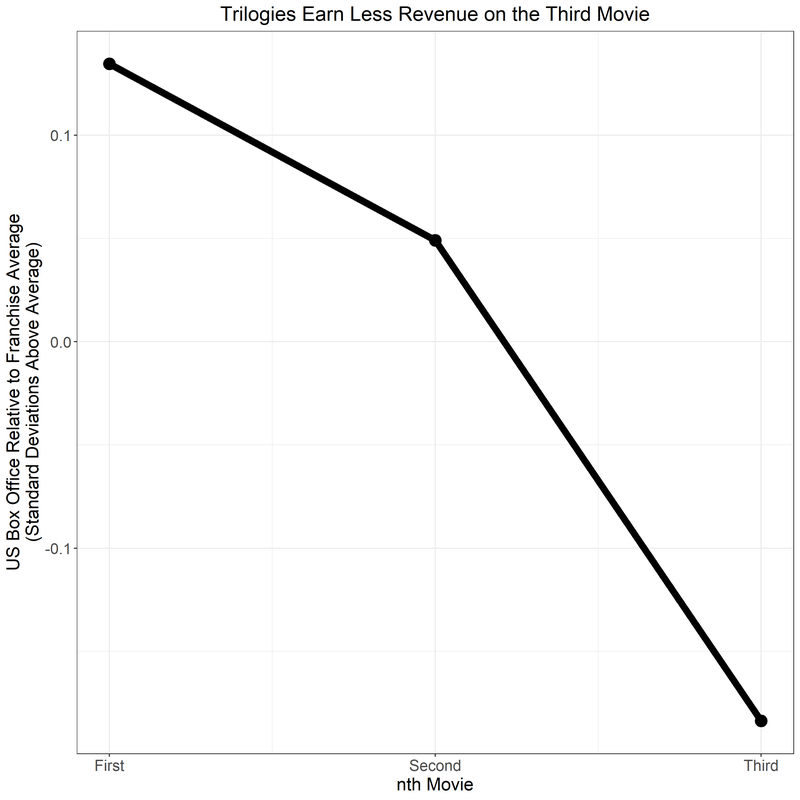

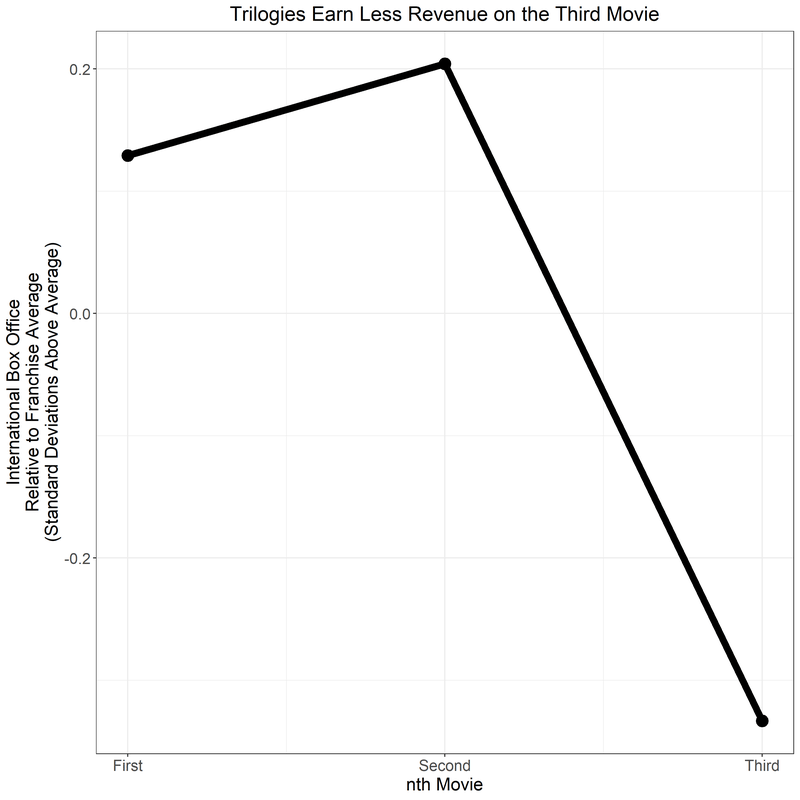

To provide a more accurate picture, we’ll present earnings in terms of standard deviations above or below the average movie in a given year, relative to the franchise average. In other words, if the first installment of a franchise made 20 standard deviations more than the average movie the year that came out, and its sequel made only 15 standard deviations more than the average in its year of release, then that decline would be reflected in the graph regardless of how the raw revenue figures compared. We’ll also separate the data into domestic and international earnings.

The two displays vary slightly, but both agree on one thing: On the whole, the first two entries in a franchise tend to earn more than the third one. That’s true even though sequels don’t get green-lit unless they’re expected to perform well.

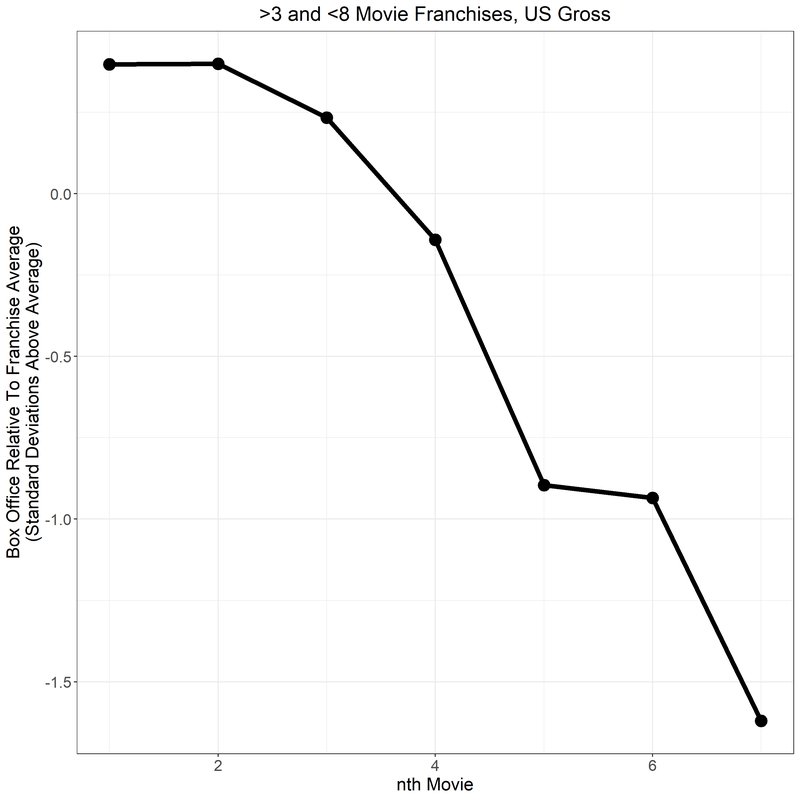

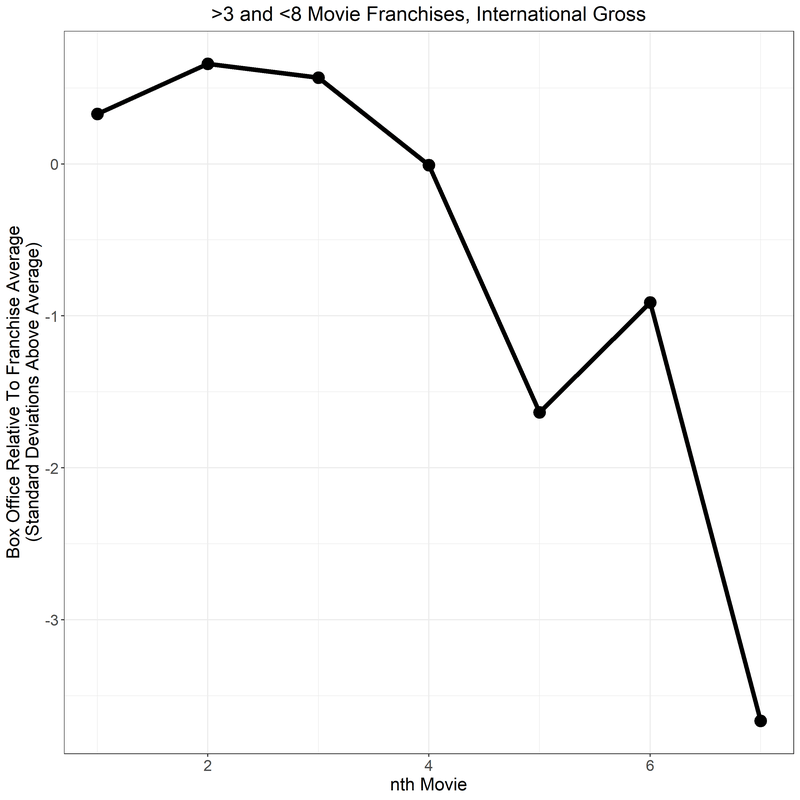

The same selection bias we warned about in our earlier three-film-franchise charts potentially also applies to these, so once again, we can unskew the sample somewhat by pulling in longer-running franchises. Once again, we see a steady decline in revenue, relative to the inflation- and marked-adjusted franchise baseline.

Admittedly, none of that means that the latter installments in veteran film franchises tend to be bad box office earners; it just means that they tend to be less lucrative than the earlier installments. (Indeed, if we compare even later franchise films’ performance to the box office baseline, instead of the standard for that franchise only, the franchise films do better—though they also typically cost more to make.) The Force Awakens made much more than The Last Jedi, which in turn made more than The Rise of Skywalker, but this is still Star Wars we’re talking about; even the last entry in that trilogy of trilogies made more than $1 billion worldwide.

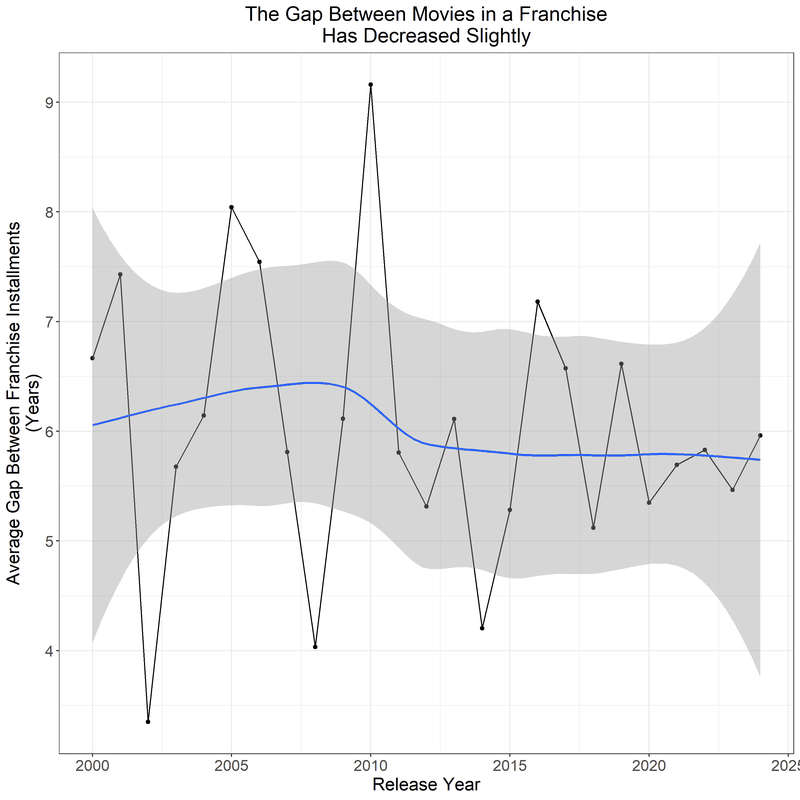

However, there aren’t many pieces of IP more powerful than Star Wars. And by trying to stretch so many series to near Star Wars-ian lengths, studios may be testing the limits of audience interest—and recall. In some cases, studios are making big bets on long memories by dredging up long-dormant franchises such as Mad Max, Beverly Hills Cop, Beetlejuice, Ghostbusters, Twister, and Top Gun, all of which went close to (or more than) 30 years without a sequel before one materialized in a more retread-friendly era. Surprisingly, despite this phenomenon of defibrillated franchises, the average time elapsed between installments of a franchise has remained roughly the same:

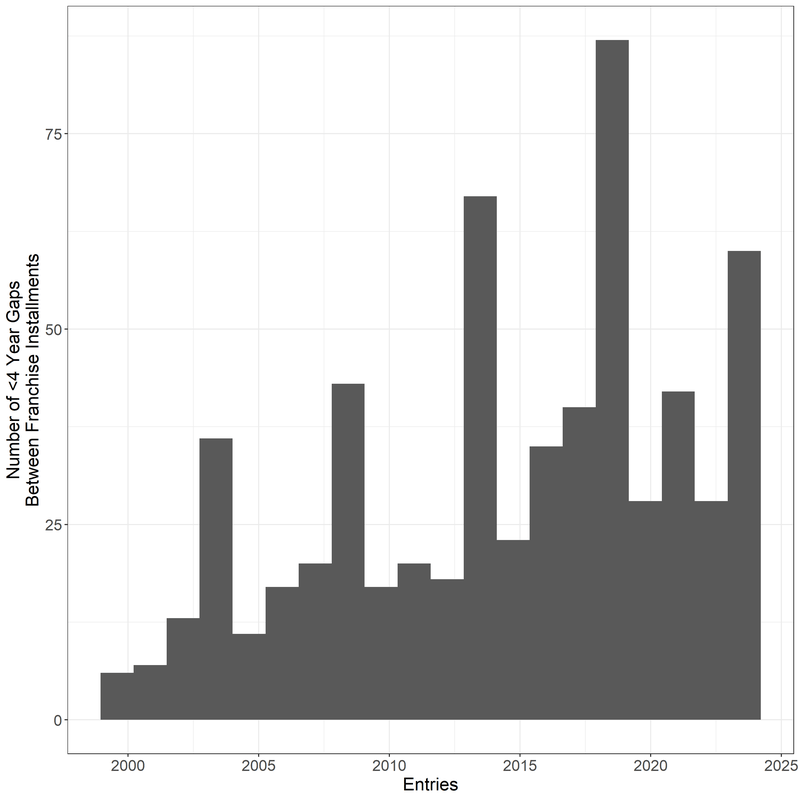

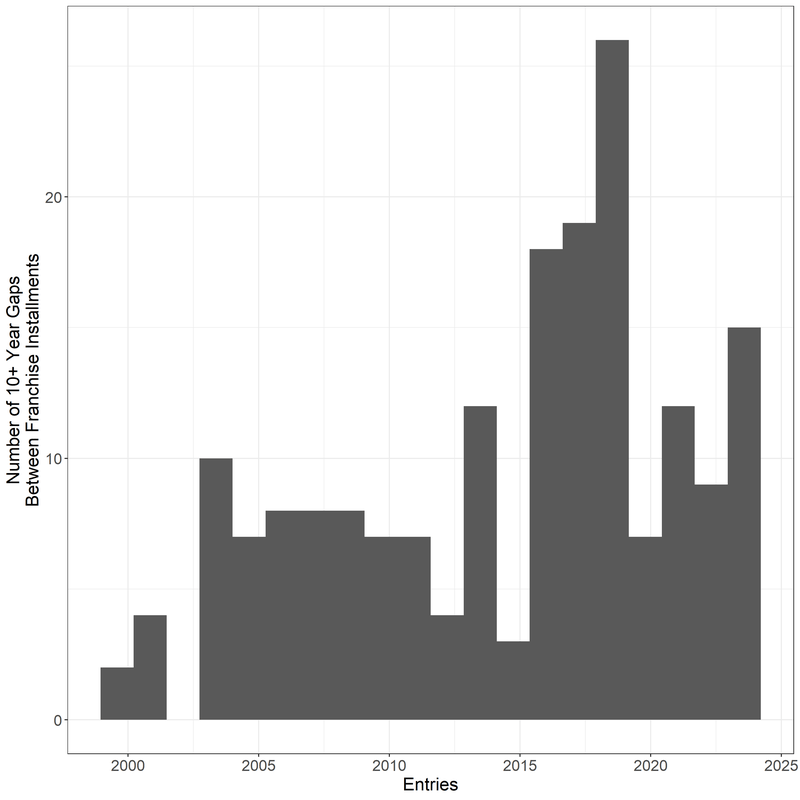

That’s somewhat misleading, though. What’s really happening is that some franchises (such as the MCU and DCEU) have dragged down the average by pumping out many movies a year, while others have inflated it by resurrecting IP that appeared dead for decades. Those two trends have come close to canceling each other out.

Studios (sort of) know what they’re doing. In a post-monocultural world with nearly limitless entertainment options, sequels, spinoffs, and reboots can be semi-safe bets, even if they’re pure nostalgia plays. But as evidenced by the doomerism that’s dogged box office coverage this year, the industry’s “Oops! All franchises” formula is far from foolproof. Quality does diminish as most franchises age, as does the public’s appetite for further installments. And the more moviemakers clear-cut existing IP rather than reseeding the cinematic landscape with story saplings that could form their own franchise forests one day, the more they risk running out of sequels that people want to watch. Which suggests that by doubling, quadrupling, and sextupling down on franchises, Hollywood may merely be slowing, not stopping, its box office decline. The longer this trend continues, the more the returns could dwindle and the more the problem could compound.