The NBA has had five different champions in the past five years. Another new winner this year would make six in six—tying the longest streak in league history. Are dynasties dead? And what will this year’s title race tell us about the state of the NBA?

More than any other major American sports league, the NBA is defined by its dynasties. A timeline of NBA history could be structured like that of a real-world imperial civilization: Mikan Dynasty, Russell Dynasty, Warring States period (Magic vs. Bird), Jordan Dynasty, and so on.

In every decade except the 1970s, at least one team won three championships:

- 1950s Lakers: 5 Finals, 4 titles (plus 1949 title)

- 1960s Celtics: 9 Finals, 9 titles (plus 1959 title)

- 1980s Lakers: 8 Finals, 5 titles

- 1980s Celtics: 5 Finals, 3 titles

- 1990s Bulls: 6 Finals, 6 titles

- 2000s Lakers: 6 Finals, 4 titles (plus 2010 title)

- 2000s Spurs: 3 Finals, 3 titles (plus 1999 title)

- 2010s Warriors: 5 Finals, 3 titles

- 2010s LeBron’s teams: 8 Finals, 3 titles (plus 2020 title)

(Perhaps including “LeBron’s teams” for the 2010s is cheating—but his extended combined run with the Heat and Cavaliers undoubtedly made him a defining figure of the decade.)

But no team has yet grabbed hold of the 2020s. The NBA has had five different champions in the past five years, starting with the 2019 title: Raptors, Lakers, Bucks, Warriors, and Nuggets. If none of those teams wins the 2024 title, that would make six champions in six years—tying the longest streak in league history, from 1975 through 1980.

The playoff field might be down to one such contender soon: The Raptors and Warriors didn’t qualify for the 2024 playoffs, the Nuggets and Lakers are facing off in the first round, and the Bucks are tied 1-1 with Giannis Antetokounmpo injured.

In other words, the Finals this June will likely bring one of two outcomes. Either the defending champion Nuggets, with a 2-0 first-round lead and growing aura of inevitability, will repeat as champions and assert their undeniable claim as the defining team of the decade—or the NBA will enter nearly unprecedented territory, without a central power around which the league’s competitive landscape revolves.

Ken Regan/NBAE via Getty Images

Nearly halfway through, the 2020s are following a comparable trajectory to the 1970s, the only other decade in NBA history without an obvious defining team. Early champions in the ’70s included a Bucks team led by a unicorn big man (Giannis Antetokounmpo, meet Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), plus two longtime, aging rivals giving their last competitive gasps (the Lakers and Celtics back then, LeBron and Steph now).

Then the NBA’s merger with the ABA in the middle of the 1970s infused it with a tremendous amount of new talent, without sufficient expansion to contain it all. That overload produced plenty of parity: In the first three years after the merger, only one team won more than 55 games in a season.

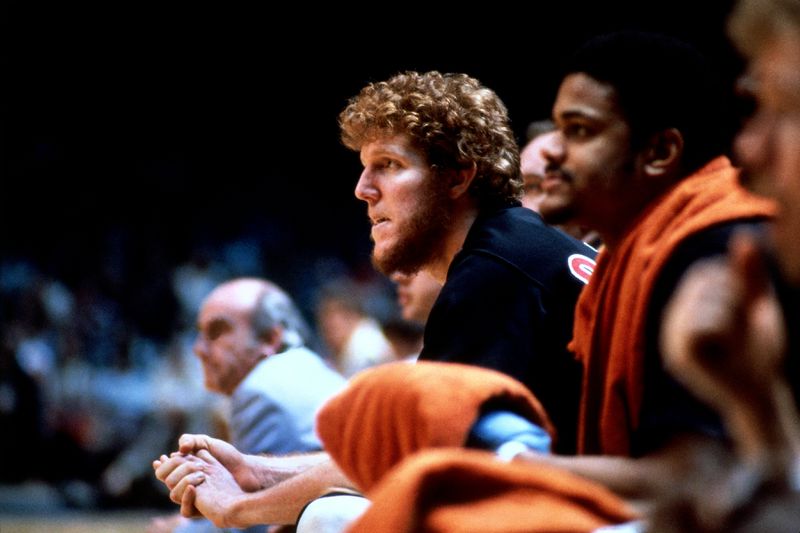

That team was the 1977-78 Portland Trail Blazers, who serve as a sobering dynastic what-if. Blazers star center Bill Walton finished second in the MVP vote and won Finals MVP in 1976-77, then won the regular-season award in 1977-78. His Trail Blazers won the 1977 title and went 50-10 in their first 60 games the next season, the third-best 60-game start in league history to that point.

Then Walton hurt his foot and the Blazers went just 8-14 over the rest of the regular season. Instead of repeating as champions, they lost to the 47-35 SuperSonics in their first playoff series. (Walton attempted to return for the playoffs, but played in just two games before departing once more.)

The future Hall of Famer played only 14 total games over the next four seasons, depriving both Portland of a budding superstar and the NBA writ large of its next dynasty. As Bill Simmons wrote in The Book of Basketball, “Walton’s injury was practically a death blow until Larry and Magic showed up.”

Bird and Magic signaled not only an explosion of NBA popularity but the return of dynasties, as well, cementing the ’70s as an anomaly rather than the norm. The NBA has less parity and more year-to-year consistency than other sports leagues for a number of reasons. Basketball is a “strong link” sport, meaning that a team’s fortunes are usually dictated by its strongest player, because it’s a team sport with relatively few players and the ability for stars to touch the ball on every possession. NBA games also have more scoring, which means less flukish variance on a night-to-night basis (as opposed to, say, soccer, where one lucky bounce more often swings results).

Those differences magnify in the playoffs. In order for the “better” team to win at the same rate as in best-of-seven series in the NBA, the NFL would need best-of-11 playoff rounds, the NHL would need best-of-51s, and MLB would need best-of-75s. It’s only natural, with this disparity, that the NBA would host more repeat champions.

In NBA history, 30 percent of titles have been won by repeat champions, a much higher proportion than in the NFL or MLB. The NHL is closer, albeit only because of long-ago dynasties.

In more recent decades, the NBA’s dynastic tendencies have remained steady while parity has increased in other leagues. Since 1990, 11 of 34 NBA champions have been repeat winners. Over the same time, 11 out of 100 champions in the NFL, NHL, and MLB combined have repeated.

But none of those repeat champions have played in the 2020s. The last team to reach consecutive Finals, let alone win there, was the Warriors with Kevin Durant half a decade ago. The only longer gap in NBA history without a repeat finalist was, again, in the ’70s, between the Lakers-Knicks rematch in 1973 and the Wizards-SuperSonics rematch in 1979.

The Raptors won the 2019 title, but didn’t have a real chance to extend their brief reign into the 2020s because Kawhi Leonard left immediately in free agency. Since then, Toronto has reached the playoffs only twice and hasn’t advanced past the second round, and with this season’s trades of Pascal Siakam and OG Anunoby, no rotation player from the title-winning roster remains in Toronto.

None of the champions from 2020, 2021, or 2022 has come close to winning another title this decade, either. The Lakers haven’t been better than a no. 7 seed since 2020; they reached the conference finals last season but were swept. The Bucks haven’t reached the conference finals in any season this decade other than in 2021. And the Warriors’ 2020s consist of one championship, one trip to the second round, and three seasons in which they missed the playoffs.

The Heat, currently tied 1-1 with the Celtics in the first round, are the only team to reach multiple Finals thus far in the 2020s. But both playoff runs were somewhat miraculous, as the no. 5 and 8 seeds in the East, and Miami has no titles and just one 50-win season this decade.

One reason for the variety of championship contenders—and therefore the lack of one omnipotent dynasty—is the NBA’s sheer amount of concentrated talent, akin to the post-merger period in the late 1970s. Even as the league has widened its talent pool by recruiting more and more international stars, it hasn’t added an expansion team in 20 years, by far the longest gap in its history. For context, in the previous 20 years (from the mid-’80s through 2004), the NBA added seven new teams to expand from 23 to 30, which better diluted and distributed talent so that dominant teams could rise.

Expansion to 32 teams is likely coming soon. But for now, if the 2023-24 Nuggets want to repeat as champions, they’ll likely have to beat four strong teams in a row, instead of being able to coast against inferior opposition for the first round or two.

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

The upcoming playoff gauntlet gives Denver the opportunity to return the NBA to its dynastic roots. Even in a more competitive Western Conference, the Nuggets, who will play Game 3 of their first-round series in Los Angeles on Thursday, remain heavy Vegas favorites to return to the Finals. After Jamal Murray completed a 20-point comeback with a buzzer-beater in Game 2, the Nuggets look nigh unbeatable in a playoff setting.

When the Nuggets won the 2023 title with a 16-4 playoff record, they became the 14th team since 1984 (when the playoff bracket expanded to 16 teams) to win the championship with four losses or fewer. The other 13 all won multiple titles in a short span.

“We’re not satisfied with this one,” coach Michael Malone said during the trophy presentation. “We want more.” GM Calvin Booth added in an interview with our Kevin O’Connor over the offseason, “It’s going to be hard to repeat. But if everything is optimized, we should win three or four.”

His team has the right core in place to do so. Nikola Jokic is the best player in the world, and he and Michael Porter Jr. are signed to long-term deals. Murray and Aaron Gordon could reach free agency in 2025; Kentavious Caldwell-Pope, who has a player option this summer, is the only Nuggets starter who could depart soon. Denver can also claim preliminary success with its plan to supplement that core with homegrown youth, with Peyton Watson and Christian Braun proving particularly useful off the bench.

Out of those seven players, six are still in their 20s, with Caldwell-Pope—probably the Nuggets’ most replaceable starter—the odd man out, at age 31.

But Booth’s “if everything is optimized” caveat is crucial. Injuries in particular could nip a Denver dynasty in the bud, just as they did to Portland’s 50 years ago: Jokic might be indestructible, but Murray and Porter both have extensive injury histories. The Nuggets might have already won multiple titles this decade if Murray hadn’t torn his ACL a month before the 2020-21 playoffs.

And while Watson and Braun are promising youngsters who could take to a bigger role in future seasons, the Nuggets don’t have a tremendous number of resources to continue adding to their roster. Denver placed fourth in our All In-dex ranking this season, as it has committed both future cap dollars and draft picks to the current cause.

Further complicating Denver’s ability to construct and maintain a dynastic roster are new rules in the NBA’s most recent collective bargaining agreement, which are geared toward the prevention of superteams. The new CBA includes harsher penalties for franchises with higher payrolls, which will restrict teams with expensive cores from adding high-caliber role players or trading for younger stars.

That effect is by design. “I’m thrilled with the level of competition, and I think what fans ultimately want is to see great competition across the league,” commissioner Adam Silver said earlier this month. “What we set out to do … was to give all 30 teams an opportunity to compete.”

Silver has referred to a “level playing field” on multiple occasions when talking about the effects of this new CBA, as in, “I’m not anti-dynasty, but you want dynasties to be created to the extent possible with a level playing field. So, if teams draft well, developed players well, trade well, but in essence operate roughly within the same number of chips, so to speak.”

The commissioner wants, in other words, equality of opportunity rather than equality of outcome—even if recent history suggests the former naturally yields the latter. The evidence is clear that dynasties in the present-day NBA are harder to come by.

It’s also possible that the next dynasty is right around the corner, but hasn’t won a title yet, with the back half of the 2020s serving as its ruling realm. At this point in the 2010s, nobody would have expected the Warriors—who were still coached by Mark Jackson and hadn’t yet reached the conference finals—to become that decade’s top team.

If not Denver, Boston is a leading contender for this long-term legacy. The Celtics posted a plus-11.3 per-game point differential this season, the fifth-best margin in NBA history, and are favored to win this year’s championship. With every key Celtic under contract for next season, a relatively young star duo leading the way, and lesser competition in the Eastern Conference, Boston could come to define another decade, like it already did in the ’60s and ’80s.

The Thunder also have a chance to own the 2020s, even though they ranked 27th in winning percentage over the three seasons before this one. Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, Jalen Williams, and Chet Holmgren form a phenomenal trio of young two-way talents, and GM Sam Presti has a hoard of future picks he can use to round out his roster. If Thunder ownership is willing to pay to keep its core together, Oklahoma City—which already won the West’s no. 1 seed with the NBA’s second-youngest team—should experience an extended run of success.

Or maybe Victor Wembanyama’s ascension will propel the Spurs to more titles, sooner than expected. Walton was only in his third season when he won his first title and almost kickstarted a dynasty; if he’d stayed healthy, Portland might have won titles in 1978 and 1979. Who’s to say the Spurs, with Wemby approaching his prime, couldn’t aim for the same in 2027, 2028, and 2029, half a century later?

Because new CBA be darned, the NBA’s broader history says that the next era-defining team is only one transcendent superstar away. This postseason will reveal whether that trend holds true for Denver, and the 7-foot Serbian who would be the next king—or whether the NBA’s long-term crown will remain up for grabs for at least another year.