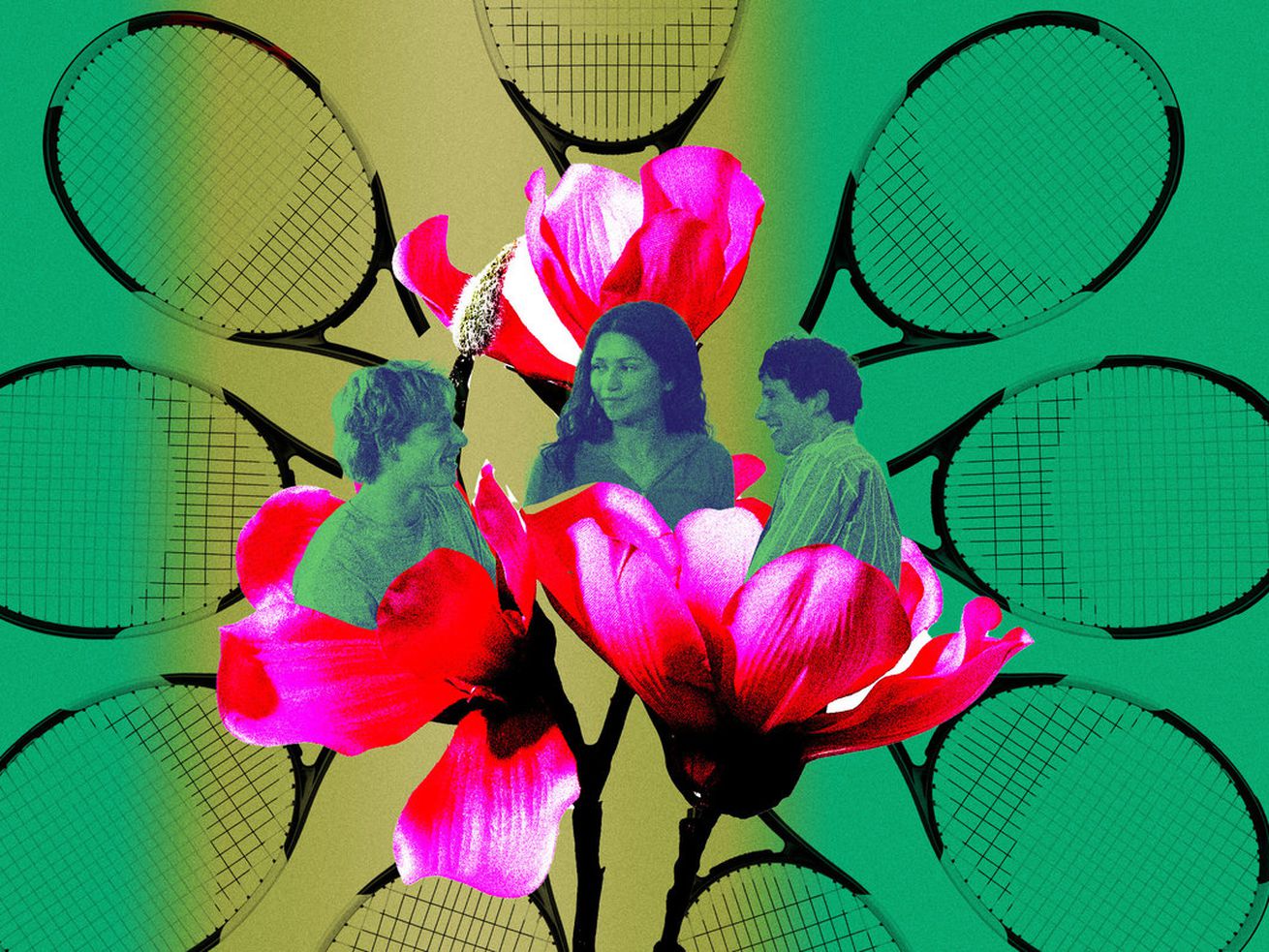

A long-awaited movie starring Zendaya and featuring threesomes, cheeky homoeroticism, and the sensation of having a tennis ball thwacked down your throat, ‘Challengers’ is guaranteed to thrill and titillate. Just maybe don’t expect it to do more than that.

Subtlety is not one of Luca Guadagnino’s virtues. The 52-year-old Italian director thrives on excess, on sequences that feel like they could suddenly spin out of control. When Ralph Fiennes’s platinum-plated record producer vamps impulsively to the Rolling Stones in 2015’s A Bigger Splash, it’s a display that feels equally true to the character’s boozy exhibitionism and the director’s narcissistic sense of showmanship; they’re both vibrating on the same ecstatic frequency, in search of emotional rescue. After more or less perfecting his florid, open-hearted style in Call Me by Your Name—a movie drenched in bittersweet sensations of love and loss, whose much-memed money shots still hold up—Guadagnino has lately cross-bred his instinct for melodrama with an unlikely (and only semi-convincing) stint as a kind of festival-circuit artsploitation specialist. In the misbegotten giallo remake Suspiria and the Twilight-adjacent YA romance Bones and All, the director drained his usually colorful palette and began treating his characters with the same tough love as a meat tenderizer; the acres of fetishistically splintered flesh on display teased a Cronenbergian mean streak. Such shock tactics were ultimately lacking, however. For all their lubricious gore (and, in the case of Suspiria, pretentious pedigree), these films ultimately felt more like designer provocations than genuine, dangerous acts of multiplex transgression.

There is one moment of body horror in Guadagnino’s new and epically hyper-extended love triangle Challengers: a knee injury suffered in the line of duty by one of its three tennis-playing protagonists. That this single, split-second bit of cartilage-busting brutality registers more powerfully than any of the bloody set pieces in Bones and All suggests that Guadagnino is back in his lane. Written by novelist (and YouTube sensation) Justin Kuritzkes—and inspired as much by Serena Williams’s infamous rage-drenched 2018 U.S. open loss to Naomi Osaka as such polyamorous classics Jules and Jim and Y Tu Mamá También—Challengers arrives as a proverbial “movie for grown-ups,” which is to say it’s a study of sexual power and frustration without a superhero in sight. It was supposed to premiere as an Oscar contender last fall at the Venice Film Festival but, under the shadow of the SAG-AFTRA strike, its producers decided to wait until a time when its stars—or maybe just Zendaya—could walk a red carpet again.

It’s not quite right to call Challengers an art movie, or even an adult one—it’s broad, commercial entertainment aimed at mainstream audiences. And it’s not subtle: The camerawork by Thai master cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom features numerous CGI-assisted shots in which tennis balls scream past our eyeballs at warp speed, as well as point-of-view shots from the perspective of the ball itself. During one key love scene, in order to underline the stormy nature of the feelings on screen, Guadagnino conjures up an actual storm—one nearly as blustery as anything in the trailer for Twisters. The effect is so goofy it’s stirring, or maybe it’s the other way around. The question is whether a director known for glossy diversions deserves points for literally throwing caution to the wind and trying to make something genuinely elemental, or whether he’s merely pumped his latest creation full of hot air.

At 131 minutes, Challengers is certainly inflated, but it moves swiftly thanks to the ace editing by Marco Costa. The cutting has to be clever in order to complement the screenplay’s structure, which serves and volleys its way through a 13-year timeline to chart the formation—and mutation—of a seductively symbiotic (and dysfunctional) three-way relationship whose participants are all equally in love (and hate) with themselves and each other. In terms of chronology, things begin with a meet-cute: soon after ascendant future singles superstar Tashi Duncan (Zendaya) meets junior doubles champions Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor) and Art Donaldson (Mike Faist) at the afterparty for the U.S. Open junior championship, she invades their hotel room and starts pushing their buttons. After coaxing the boys into some mutual fooling around—sitting up straight like a line judge between her groping suitors—she proclaims that she’ll consider dating the winner of their upcoming one-on-one match.

“I don’t want to be a homewrecker,” Tashi says before she goes, but that’s exactly what she wants to be, and not just because it turns her on. An obvious prodigy with Serena-sized ambitions, she’s drawn to talent, and senses that Patrick and Art are too cozy to get the best out of themselves. (The first time we see them hanging out together, they’re gobbling hot dogs: 15, Guadagnino; love, subtlety.) Since the characters are all ego-stroked up-and-comers exploring their adult emotions—and their perfect, precision-tuned bodies—such naughty manipulation is all in good fun, a night to remember when they’re older. (“I’d let her fuck with me with her racquet,” says Patrick in a wry bit of figurative foreshadowing.) Cut to the present tense, though, and the trio’s mixture of intimacy and solidarity has exploded, along with their respective personal and professional aspirations. Both men have had a crack at dating Tashi, with Art managing to stay in her good graces as a long-time partner—but only because her own career has stalled. Patrick, meanwhile, has fallen off the map, only to strategically resurface at a podunk tournament where he vows to be a thorn in his old pal’s side. Suffice it to say that questions of winning and losing look very different in one’s 30s than in one’s teens, and also that the same competitive spirit that drives people toward greatness can also plunge them into abjection.

Defeat and disarray are qualities squarely within O’Connor’s wheelhouse; the British-born actor was brilliant last year in Italian director Alice Rohrwacher’s La Chimera playing a rumpled archaeologist whose preternatural ability to locate lost artifacts hasn’t helped him find himself. Here, he inhabits Patrick’s mercurial nature with just the right amount of self-deprecating humor, as if he’s amused by his own running tendencies toward sabotage. Muscles bulging and eyes gleaming with appetite, he’s the ideal foil for Faist’s slender, soulful Art, who’s too anxious about his talent (or lack thereof) to ever consider becoming his own worst enemy: where his rival laughs off encouragement, he thrives on it, but never seems fully satisfied by the results. (Faist, who has a Broadway performer’s rakish sense of razzle-dazzle, comes off here as a pensive puppy dog, while O’Connor is a cool cat.) Each man is, in his way, a sitting duck for Tashi, whose supreme passion is not for sex, but tennis—a sport whose pounding back-and-forth nature offers the only plausible outlet for her pugnacious stamina. Watching the young Tashi stalk around the court in between points is like National Geographic channel footage of a predator in action; it also recalls Mitch Hedberg’s line about how no matter how much one masters tennis, they’ll never be as good as a wall: “That motherfucker is relentless.”

Zendaya’s stardom, meanwhile, is itself a byproduct of relentlessness—a phenomenon that’s routinely insisted upon more than it is illustrated on screen. It’s not that the potential isn’t there. Rather, she possesses such an obviously impressive package of poise, beauty, and talent—topped off with the willingness, exemplified by her work on Euphoria, to go to dark places—that it’s easier to simply anoint her as a generational performer than judge her work. What does it say that many of her most memorable moments have come on red carpets, or during promotional junkets (or while being upstaged by Tom Holland on Lip Sync Battle)? For the most part, her movie roles have either been boringly ornamental—playing expectant, supportive, dramatically sidelined love interests in franchise IP (Spider-Man, Dune) or would-be tour-de-forces undermined by bad material (see Malcolm & Marie, if you dare).

With Challengers, Zendaya finally has a part that could potentially turn her into a modern screwball goddess (or, more to the point, she’s crafted one in her capacity as a producer). There are scenes that work beautifully, like the early make-out routine, which vibrates with sly, deadpan eroticism. Mostly, though, the performance suggests an actress in search of a real character. It’s one thing for Tashi to sell herself to the men in her life as a streamlined, eyes-on-the-prize cipher—it’s a good way to string them along and keep herself at a remove—but as the movie goes on, it’s clear that Kuritzkes doesn’t have much of a sense of what makes Tashi tick beyond some abstract (and cartoonish) notion of excellence. We never really get a sense of how she feels to be a wife or a mother (roles she inhabits only in brief, perfunctory glimpses); the movie is obviously much more interested in the lost, sulky boys bobbing in her wake.

This would be fine if Challengers were as attuned to the rituals of male rivalry as, say, Ron Shelton’s White Men Can’t Jump—still one of the great American movies about competition, and one that uses sports as a kind of divining rod to tune into larger cultural frequencies. That movie shows us, time and again, how basketball contains multitudes: it’s a showcase for fashion; a melting pot for racial tensions; a series of contrasting and complementary philosophies. Challengers tries to make the same all-encompassing point about tennis—a thesis that frames life (and love) as a series of hard, hostile volleys, and reduces the world beyond the court to a blur (there’s not nearly enough here about the culture and customs of the pro tour, for instance). In purely kinetic terms, the climax may be the best-executed scene of Guadagnino’s career, surpassing Suspiria’s grotesque ballet recitals. But the only thing really pressurizing the action is style—it’s hard to truly care about characters when they’re at the mercy of such mechanical storytelling contrivances.

“Tennis is a conversation,” says Tashi, as Patrick and Art drool in response. It’s a good line, but it also unintentionally gets at the essence of this appealing and well-made movie’s failure—the way its particular kind of filmmaking eloquence ends up saying almost nothing at all.

Adam Nayman is a film critic, teacher, and author based in Toronto; his book The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together is available now from Abrams.