Oakland has become a new center of sports fan activism. But with the A’s headed to Las Vegas, what are the fans there still fighting for? Why should fans elsewhere care?

Opening Day possesses a ritual significance for baseball fans. Writing in The New York Times in April 1963, Roger Angell described Opening Day as “a ceremony of renewal and welcome” whose meaning, for baseball fans, is “psychic and profound”—an Easter in the church of grass and sky. This, Angell was suggesting, is true for all baseball fans every year—but I think he would have conceded that it was perhaps especially true for fans of the Oakland A’s this year. Twelve months ago, John Fisher, owner of the Oakland Athletics, Oakland’s last major league sports team, revealed that he would move the A’s to Las Vegas in 2028. This was bad enough, but then, this February, rumors started swirling that Fisher intended to move the A’s out of Oakland much sooner than that—to Sacramento, at the end of 2024. The ceremony of renewal and welcome would need to be reconfigured into a wake. Opening Day 2024 would be the last Opening Day Oakland fans would probably ever get.

Oakland fans recognized the occasion in predictably Oakland fashion—not by mourning, but by boycotting the game and instead throwing a massive tailgate party and political fundraiser in the Oakland Coliseum parking lot.

And for the party, they went all out. There were cornhole tournaments and face-painting stations, food trucks and homemade carnival games. (A favorite featured target galleries challenging contestants to huck beanbags at caricatures of Fisher, A’s team president Dave Kaval, and MLB commissioner Rob Manfred.) There were makeshift stages for two separate Mexican street bands and rows of amps discharging a constant bracing rumble of Keak Da Sneak, Mac Dre, E-40, and Luniz. Apparel company Oaklandish was there handing out kelly-green SELL flags that fans fixed to PVC pipes and to the tailgates of their trucks, and that by sunset were snapping hard in the breeze by the hundreds, like the unfurled banners of some parked Celtic horde. There were portable grills set up beside open coolers in little asphalt campsites all across the lot. Hal the Hot Dog Guy was walking around in a possum suit. Former Oakland mayor Jean Quan showed up with a cake she’d baked.

Fans gathered before the makeshift stages for speeches. They danced, flaunted costumes and vintage gear, and partook in cathartic “Sell the team!” chants that rattled the cars. They carried signs—Fisher lies; Rot in hell Fisher; Fisher did 9/11—and trumpeted like elephants into their plastic vuvuzelas. The security assigned to the Coliseum parking lot to monitor the proceedings turned out to be A’s fans who ate tacos with the attendees. Event organizers had tethered a giant inflatable TV screen to the portable bleachers that Coliseum ground crews used to haul into center field before Raiders games, and they projected on it that evening’s matchup, against the Guardians, so that fans could watch without going inside. As darkness fell, fans huddled close around it, the game glowing against their faces.

Oh, and you can believe there was beer and wine and liquor and no small number of joints getting graciously passed around, like plates at a potluck. (Your correspondent, out of professional duty, bit his lip and declined.) Everyone was hard at work having a good time. Though, of course, they were there to do more than just have a good time. They were there to make a statement—and perhaps even a difference.

That, at least, was the goal of the boycott’s organizers, among them Bryan Johansen and Jorge Leon. Johansen is the cofounder of Last Dive Bar, an Oakland A’s supporters group turned apparel company and philanthropy organization. (Johansen estimates that they’ve raised a quarter of a million dollars for local charities over just the past few years.) Leon is the East Oakland–raised, democratically elected president of the Oakland 68s, a supporters group styled in the vein of European soccer fam clubs. It has a board and counts more than 1,000 members.

Johansen and Leon make somewhat odd bedfellows. Johansen is burly and jocular, a former high school prom king and collegiate first baseman who bashes through conversations like a Labrador through shrubs. Leon is lean and competitive and does not often remove his black aviator sunglasses. Last Dive Bar got its start making memes and selling merch and remains grounded in good humor. The 68s are more combative; like Leon, its members have been protesting the flightiness of A’s ownership, sometimes getting escorted out of games for doing so, since the early 2000s. The spray-painted bedsheets you see strung like SOS flags above the out-of-town scoreboards? That’s them.

Nevertheless, Johansen and Leon started their respective groups in the 2010s with similar goals: to advocate for the interests of Oakland sports fans, as well as to celebrate and revel in all that is singular about Oakland sports culture—its blue-collar affability and iconoclastic funk, an egalitarian melding of countercultural cool and scrapyard might. And when the A’s started intimating, in 2021 and 2022, that they might relocate, the groups switched tacks in lockstep. Out was the boosterism. In was readiness for war.

At first their resistance mixed activism with advocacy and hope—the goal, as Leon put it at a rally last fall, was to convince Fisher to “do the right thing: build [in Oakland] or sell the team.” Later, some fans started advocating more specifically for MLB to earmark an expansion team for Oakland, or for MLB to force Fisher to leave the A’s likeness and history in Oakland after the team inevitably left—as Art Modell had left the Browns’ history and likeness in Cleveland when he moved the Browns to Baltimore in 1995. But the goal hardened into its present form when it became clear to fans that Fisher had no intention of doing “the right thing”—and that nobody, MLB least of all, would be coming to save the team.

Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

A goal of the movement is still “to promote the sale of the team and make Oakland’s case as the best place for the A’s to be,” Johansen told me over lunch a few days before the boycott. We were eating burritos outside the Tesla factory in Fremont, where he works as an engineering technician. “But more so, we want to expose the A’s on a national level and hold Major League Baseball accountable for what they’ve condoned.” The object of fans’ ire is not only the rich guy taking away their team. It’s the culture and industry of professional sports that enabled him to do so.

Today, Last Dive Bar and the 68s provide the manpower for what has become nothing less than a full-blown fan activist movement, with a charter that transcends both the A’s and Oakland. “Our end goal is not to keep the A’s in Oakland,” Leon told me. “We want real change.”

Though, of course, virtually every A’s fan I’ve spoken to over the past year told me they’re at least equally motivated by something less constructive, less altruistic. What was that motivation? I asked Johansen. He chomped into his burrito. “To fucking haunt John Fisher for all of eternity.”

In case you aren’t caught up with why A’s fans might want to haunt Fisher for eternity—beyond his relocation of their city’s only remaining major pro sports team—here’s as brief a summary as I, myself a longtime A’s fan and East Bay resident, can muster.

The first thing to know about Fisher is that he’s very rich—dynastically rich. He’s the youngest son of the cofounders of Gap. Forbes has his net worth at nearly $3 billion. The second thing to know about him is that he is, as ESPN’s Tim Keown put it, “singularly uncharismatic.” When he purchased the A’s in 2005, though, his wealth lent him a sort of distortive sheen. The team was, at the time, one of pro sports’ most infamously frugal franchises, an organization so perpetually, pitifully poor that a movie was made about it. But A’s baseball isn’t cosmically intertwined with Moneyball. The franchise once boasted the highest payroll in Major League Baseball and some of its most exciting teams, and had among its best attendance rates as a result. For fans, it was possible to hope that Fisher would restore to the A’s a level of investment and respect befitting their history.

The opposite occurred. Fisher invested virtually none of his own money into the club—the biggest free-agent contract he’s ever extended was to Joakim Soria, for $15 million over two years—and even less in the way of personal energy or interest. (Evidence suggests he might not know the names of any A’s players or coaches.) When his teams won, it was in spite of him. A native San Franciscan, he seems to view the community his team technically still represents with a kind of contempt.

After the Raiders and Warriors both left Oakland, in the late 2010s, he at least seemed to want to stay in Oakland—but even then only if the city forked over some $855 million in public funding to finance a privately owned development on the West Oakland waterfront. When Oakland, which was still paying off the debt it’d taken on the last time it was asked to mortgage its future on professional sports, tried negotiating Fisher down to a slightly less ruinous sum, he embarked on a new project: proving Oakland sports was broken by breaking it himself.

Fisher had already made some progress to this end, over the years—constantly trying to move your team out of town while letting every one of your organization’s good, identifiable players go does not a loyal fan base make—but what happened next made the before times seem blissful. Have you ever seen a young child crudely, absentmindedly dismember a doll? That’s what Fisher did to the A’s. In a span of roughly four months, starting in the fall of 2021, he turned the team into the worst organization in sports. He took a sledgehammer to the team’s payroll—the A’s Opening Day payroll this year was a full 24 percent lower than that of the league’s second-cheapest team—then, remarkably, raised ticket prices. He allowed the Coliseum, which he’d convinced Alameda County to sell him half of in 2019, to fall into disrepair; early on in 2023, it was discovered that a possum had made a home for itself in the visitors’ broadcast booth. The A’s brusquely severed ties with the East Bay community, including groups like Last Dive Bar, which had worked with the team on marketing initiatives and charity events; Johansen told me that after the A’s had decided to relocate to Vegas, in 2023, the organization ghosted them. He says that broadcasters were told not to reach out or mention Last Dive Bar on air. Executives stopped texting them back.

Then—then!—after the deal to move the A’s to Vegas had been finalized, Fisher, with the help of Manfred, tried gaslighting Oakland fans into believing it was their fault the team had to move. “We have shown an unbelievable commitment to the fans in Oakland by exhausting every opportunity to try to get something done in Oakland,” Manfred said at a press conference last spring, about the A’s move to Vegas. “But you don’t build a stadium based on club activity alone. The community has to provide support.” Never mind that Fisher had spent the first 12 years of his tenure trying to move the team first to Fremont and then to San Jose, and that Oakland had offered him more than double the amount of public funding for his lavish development dreams that Carson City did. In the fall of 2023 Leon and a pair of documentary filmmakers flew to Arlington for the MLB owners meeting, where he confronted Fisher directly. Fisher responded, self-pityingly and in all sincerity, “It’s been a lot worse for me than you.”

Now, on top of it all, the A’s are ditching Oakland earlier than expected for a minor league park in Sacramento. After the team’s press conference announcing the move, Kaval, the team president, remarked that, as part of the relocation, the A’s would be laying off most of their staff.

Much like the decision to leave Oakland for Vegas in the first place—why ditch the country’s 10th-biggest television market, where the A’s have put down roots nearly 60 years deep, for less public money in what will be MLB’s smallest market?—the move to Sacramento bewildered A’s fans as much as it broke their hearts. As Keown put it, “It would be easier for the people of the East Bay to understand” what had been done to them “if someone, anyone, involved in making [the decision to relocate] could come close to making a coherent argument for why it’s happening.”

Few fans like the person who owns their favorite team. Further, as David Samson, former president of the Miami Marlins, told me, “Relocations are always clumsy and hurtful,” and it’s not unusual for owners to pit cities against each other as part of facilitating them. “I used other cities as leverage,” he said, “to get a deal done in Miami.” Still, the cynical razing that Fisher subjected Oakland to stands alone in the hierarchy of shitty owner behavior.

But if Fisher stands alone for his treatment of A’s fans—or for how terribly he ran A’s baseball—he’s not unique in the way he’s sought to turn public funds into private profits. How many other teams—in places like Phoenix, Kansas City, Chicago, and beyond—have toyed with relocation in just the past few months? More will yet.

Which raises a question: What would you do if someone hollowed out and held for ransom your favorite team? Thanks to pro sports’ cultural might and some fun quirks of the American legal system, which allows team owners a state-sanctioned license to do with those teams whatever they please, it might seem like there’s nothing to do. But in fact, there is a long history of fan bases that have pushed back against aspects of our relationship with sports they deemed unfair or illogical.

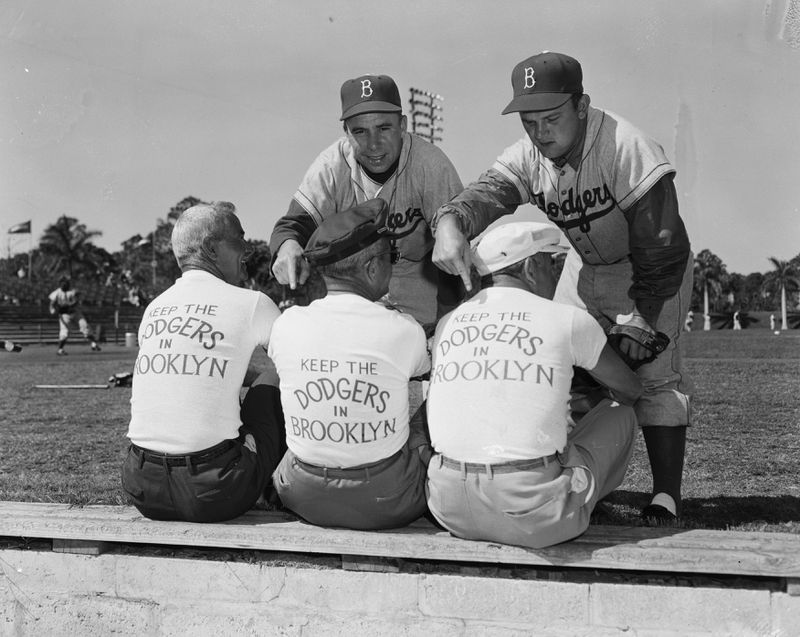

Like in Brooklyn, where a group of businessmen formed the “Keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn” committee in 1957 to prevent the abdication of their beloved Dodgers from their hardscrabble borough. My, how times have changed since then. Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley was trying to convince New York City’s Parks and Recreation commissioner Robert Moses to condemn a specific—and expensive—piece of land at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues and grant it to O’Malley, to allow the Dodgers to build a privately funded stadium. Moses refused (“I don’t think that a privately owned ballpark fulfills a public purpose at all, and I’m not going to use Title I [of the Federal Housing Act] to get you this land. If you want the land, buy it like everybody else would,” Moses reportedly told O’Malley). O’Malley had other options, namely Los Angeles, where city officials offered him 300 acres of land in exchange for a commitment from O’Malley to build a stadium on the site and the deed to Wrigley Field in Los Angeles.

Getty Images

The committee’s goal, as outlined in a letter to Brooklyn’s newspaper, The Tablet, was to convince Moses to stay in Brooklyn. For months the group went door-to-door, imploring residents to sign petitions. They organized rallies outside Brooklyn Borough Hall. A song—“Let’s Keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn”—was even performed by Phil Foster on The Ed Sullivan Show. Moses, however, remained unswayed. The Los Angeles Dodgers are now the second most valuable team in baseball. Brooklyn still doesn’t have a team.

Fans have also fought for more than just teams, for things like symbols, history, and community spaces. Like in 1980s Detroit, when fans created the Tiger Stadium Fan Club—a grassroots campaign to save Tiger Stadium from demolition. Since its construction in the 1910s, Tiger Stadium had functioned in Detroit as something more than just a ballpark. Rather, it was a rallying point and a landmark, a concrete-and-steel representation of Detroit’s industrial muscle and even of baseball’s urban soul. Tigers ownership wanted to tear it down and build something shinier. The Tiger Stadium Fan Club was started in 1987 by a group of fans as a way to stop them.

The club was relatively humble at first. At its first public meeting in 1988, at the Gaelic League Irish American Club, 200 people showed up. Later that year, however, the club orchestrated a now-famous “Stadium Hug,” in which 1,200 Tigers fans gathered at Tiger Stadium on the 76th anniversary of its opening to encircle it with their arms. And they didn’t stop there. They took out ads in the paper. They gave interviews on TV. And it all seemed to pay off. In 1989, Tiger Stadium was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. (Though victory was short-lived. Tigers owner Tom Monaghan—the founder of Domino’s Pizza—and a slew of city officials desperate for new development downtown sprung up new campaigns designed to persuade the public of the urgent need to replace Tiger Stadium with a publicly funded modern park. The Tiger Stadium Fan Club responded by boycotting Domino’s and expanding the scope of its efforts. The club even led a successful campaign to put the issue of using public funds for stadium construction on the ballot. On March 17, 1992, residents voted against the idea by a 2-1 margin. Not long after, however, the Tigers were sold to a separate pizza baron, Mike Ilitch of Little Caesars, who, though a lifelong Tigers fan, was also—as Neil deMause and Joanna Cagan report in their invaluable text on stadium swindles, Field of Schemes—a “downtown developer whose ties to the city development cabal ran deep and strong.” Within just a handful of years, he and his political allies had overturned the referendum, acquired funding from the state and from Detroit, and initiated a full-court media press centered on all the typical talking points that team owners, league bosses, and pocketed politicians trot out in support of subsidized stadium projects, like talk of jobs, new tax revenues, and more development. Construction on Tiger Stadium’s replacement, Comerica Park, began in October 1997.)

But fan-activist efforts are not always futile. Take the Save Our Browns campaign in Cleveland. In November 1995, news broke that Art Modell, the Browns’ owner, had entered into a secret deal to move the Browns to Baltimore, where he’d been offered a publicly funded stadium and the chance to play there rent-free. Browns fans, who ranked among the most vociferous in sports—the Browns Backers, a fan group, still claims to count 70,000 members globally—took offense to the move. They hung signs reading STOP ART MODELL on billboards and freeway overpasses all over the city. They wrote letters to the NFL. They caravanned from Cleveland to Pittsburgh for a protest outside a Browns-Steelers Monday Night Football game. They enlisted comedian Drew Carey to help them put on a “Fan Jam” at Jesse Owens Park, which was followed by a march up West 3rd Street toward Cleveland Stadium. They were relentless—dogged, some would say—and it worked. They didn’t, in the end, stop Modell, but at least in part due to their efforts, Modell agreed to leave the Browns’ history and likeness in Cleveland, where they could be adopted by a future expansion team, which was almost as good. At the first practice the expansion Browns held, in the spring of 1999, more than 30,000 fans showed up.

Then there’s the case of Kings fans in Sacramento, who achieved in 2013 precisely what A’s fans were working so hard to do last year: they successfully stopped a relocation effort. The Maloof family, who owned the Kings, were all set to sell the team to an ownership group that wanted to take it to Seattle. Fans organized, forming groups like Crown Downtown, which showed up at city council meetings.

Fans also took more extreme measures, such as the cross-country RV tour that Carmichael Dave led from Sacramento to New York ahead of an owners meeting convened to discuss the Kings relocation. Dave decked out a 32-foot RV in white and purple Kings decor and made stops in more than 20 cities along the way, prioritizing those with NBA teams whose owners were on the league’s relocation committee. When the RV finally reached the St. Regis in midtown Manhattan, Dave and the Kings fans with him piled out and started chanting, “Here we stay!”—the rallying cry of their effort. Dave told me that the owners could hear the chants inside the presentation room. The relocation committee voted 7-0 against the sale. Not long after, the Maloofs instead sold the team to Vivek Ranadivé, a buyer who intended to keep the team in town. Three years later, the Kings moved into the publicly funded Golden 1 Center, downtown.

According to Leon, however, the supporters groups that Oakland fans have drawn the most inspiration from are those in Europe that, three years ago, thwarted the formation of the so-called Super League. The Super League was to be a new elite soccer competition. It was the brainchild of the owners of 12 of Europe’s richest soccer clubs. The point of the Super League was permanence and control. There would be no relegation, as there is in top-tier domestic competitions like the Premier League, and teams wouldn’t have to play to get in, as they have to do in the Champions League or for the World Cup. The Super League’s founding members, as The New York Times reported, would “face no risk of missing out on either the matches or the profits.” The Super League would be a lot like MLB or the NFL in this sense: closed monopolies. And as in MLB and the NFL, the profits figured to be massive. The broadcast rights alone—which member owners would not have had to redistribute to smaller clubs or lesser leagues—would have been worth billions.

Pretty much the instant that owners’ plans for the Super League were announced in 2021, fans revolted. There were outbursts of outrage outside Stamford Bridge in southwest London, where the Chelsea Supporters’ Trust surrounded and marooned Chelsea’s team bus before a match against Brighton & Hove Albion, screaming, “You greedy bastards, you’re ruining our club.” In Leeds, Liverpool supporters joined with Leeds United supporters for a demonstration outside Elland Road, where they tried to stop the Liverpool bus from entering the grounds. Statements were put out by the Arsenal Supporters’ Trust, which said that the Super League represented the “death of everything football should be about”; by the Spirit of Shankly, which suggested that Liverpool’s owners, Fenway Sports Group, had “ignored fans in their relentless and greedy pursuit of money”; and by the Football Supporters’ Association, which represents supporters in England and Wales and posted a statement reading, “The motivation behind this so-called Super League is not furthering sporting merit or nurturing the world’s game—it is motivated by nothing but cynical greed. This competition is being created behind our backs by billionaire club owners who have zero regard for the game’s traditions and continue to treat football as their personal fiefdom.”

Photo by Rob Pinney/Getty Images

Fans’ fury influenced governments. In England, Prime Minister Boris Johnson promised to try to thwart the Super League’s formation by dropping a “legislative bomb” on the project. Chelsea pulled out not long after. Then Manchester City. John Henry, owner of Fenway Sports Group, apologized to Liverpool fans with a video message: “I’m sorry and I alone am responsible for the unnecessary negativity brought forward over the past couple of days. It’s something I won’t forget. And it shows the power the fans have today and will rightly continue to have.”

From the beginning, Leon, Johansen, and the rest sought to prove that fans in America have this power, too. Though it took them a minute to figure out exactly how to do it.

In May 2023 (a month after news of the Vegas relocation dropped), I attended Last Dive Bar’s Rotten Tomato Tailgate, a small event in the Coliseum’s north lot. Fans were invited to throw tomatoes at plywood effigies of Fisher, Kaval, and Manfred. It was a strange time, then. A’s fans from across the East Bay were still in a kind of mourning and slightly stupefied, and only a few hundred partook. The media treated it mostly as a curiosity.

The following month, however, Last Dive Bar and the 68s collaborated on what became known as the “reverse boycott,” a show of force that nearly 30,000 people showed up to. The idea was to refute the pretense about the languishing A’s fandom that Manfred and others had floated as a reason to move the team. The fan groups succeeded in showing their might and numbers. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Scott Ostler called it “one of the great protest moments in the history of the Bay Area.” One of the kelly-green “Sell” shirts that Last Dive Bar and the 68s distributed in the Coliseum parking lot before the game has been kept by the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Throughout the summer the groups organized additional demonstrations with similar goals, including at the 2023 All-Star Game in Seattle and the Battle of the Bay series in San Francisco. The groups grew bolder and more strategic as well. In November, ahead of an owners meeting in Arlington where they were expected to vote on the A’s relocation application, Leon and the 68s led a rally in the city council chambers of Oakland’s City Hall. Before a crowd—clad in green shirts reading “STAY” and “SELL” that the 68s had handed out on the front steps—and flanked by the mayor, port officials, and members of the Oakland City Council, Leon took to the dais and gave a speech. “Oakland … has shown tremendous willpower, no matter what the commissioner has said,” he bellowed into the mic. He cut the air with his hand as he spoke. “We’re asking MLB owners to vote no [to] relocation.” Shortly after, Leon traveled to Arlington, both to confront Fisher and to make his case to arriving MLB owners directly.

The owners ended up voting unanimously to approve the relocation. But A’s fans didn’t stop their protest efforts. Instead, they set their sights on their next event: a fan-organized Fans Fest, to be timed to the start of spring training. (The groups had to throw their own fest because the A’s stopped throwing such events several years ago.) They held it at a cordoned-off intersection in Jack London Square. They had live music, beer vendors, a silent auction, games for the kids, and food from all over the city. Somewhere in the ballpark of 20,000 people showed up, including the mayor and former A’s players: Ben Grieve, Coco Crisp, Trevor May. Also present was former A’s closer Grant Balfour, who near the end of the festival took to the rostrum and affirmed to the small sea of green before him, “Not one person here deserves this team to leave. … You are the most creative fans in MLB.”

Recent efforts have shown yet more creativity. Last month, Last Dive Bar, alongside Hal the Hot Dog Guy—otherwise known as Hal Gordon, the former hot dog vendor turned economist who’s involved with both Last Dive Bar and the 68s—prompted their followers to write letters to Alameda County representatives and Oakland City Council pressuring them to “Stop Fisher’s Coliseum Bailout”; to date, more than 33,000 letters have been sent. Last Dive Bar also applied to trademark the term “Las Vegas Athletics”—before, evidently, Fisher had thought to do the same.

In the 12 months since their activist efforts really picked up steam, A’s fans have been heralded by commentators across the sports world for their perseverance and pluck—their industriousness, gamesmanship, and grit. The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal called what A’s fans have done “something to behold.” Scott Braun, cohost of the podcast Foul Territory, told me, “In a world where something becomes old news after 24 hours, A’s fans have kept this story in the public sphere. … A’s fans have universal respect across baseball.”

In a way, though, the groups’ previous efforts all culminated in the Opening Day boycott. I tagged along with Johansen, Leon, Gordon, and the rest as they set about planning it. They outlined three strategic objectives. First, they wanted to make sure fans had a good time. “Going to an A’s game doesn’t feel good anymore,” Johansen told me. “You go and you feel dirty. The first thing we want the boycott to be is an opportunity for fans to feel good and to remember that they belong to something they can be proud of and happy about.”

Second, they wanted to raise money for Schools Over Stadiums, a political action committee representing the Nevada State Education Association that’s working to hold a referendum on the public funding Fisher secured last June. A majority of Las Vegas residents oppose the subsidy. The hope for Oakland fans was that if Fisher’s stadium deal fell through in Nevada, he might have to sell the team—perhaps to a certain beloved local buyer. Schools Over Stadiums needed money for legal fees—according to Schools Over Stadiums, a group with ties to the A’s sued the organization last fall—and for a signature-gathering campaign. The committee’s founders would be at the boycott. Last Dive Bar had recruited volunteers to solicit donations on their behalf.

Perhaps most of all, however, they wanted the boycott to make a point. About Oakland fans and the truth of what they say Fisher had put them through—“I want the whole world to see what this individual is sacrificing solely for his personal gain,” Todd Saran, the 68s treasurer, told me—but also about the business of American pro sports, and this rotten thing at the core of it that Oakland had become uniquely, unfortunately acquainted with.

Bizuayehu TesfayeLas Vegas Review-Journal/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

What is the rotten thing? Everyone who loves a sports team or who once loved a team or who has even just lived in a place that was momentarily swept up by the heady swell of a playoff run or pennant chase knows well what the relationship between sports and place can be like—how beloved pro teams can elevate both the perception and the experience of a place. How they support community spaces and create culture. We know, too—have seen, in particular in places like Oakland—how cities can prop up, inspire, and meld with teams. This is a part of sports worth celebrating, worth investing in, worth giving time to and fighting for; it’s what Leon and Johansen and all the rest have been fighting for all this time in Oakland: the potential of pro teams to create partnership and symbiosis. Leon and Johansen had both felt this in their own lives. Most of us who love sports to a degree that might strike others as irrational have. It’s what Roger Angell saw as the primary thing worth recognizing about Opening Day, “a celebration of the simultaneous return of springtime and baseball time … and a noisy, cheerful restoration of the bonds of loyalty and affection that bind the fans to their home club, and vice versa.”

Yet more and more, owners like Fisher are making American pro sports a little less like this, less romantic and reciprocal, and more about profits, and power, and the cartel politics by which the two are consolidated. Leon and Johansen saw the boycott, much like the other large-scale demonstrations put on before it, as an opportunity to bring more attention to these ascendant predatory and extortive elements of sports—as well as to show other fan bases what they can achieve, change, or restore when they’re organized. Is it possible to restore some more concrete sense of reciprocity and partnership to our relationship with sports? Can sports be made to live up to their romantic civic potential once again? A’s fans believed they could—even if it was too late for them to do so. “Fans have rights and power, too,” Leon said. “But fans need to know their unity is their strength. We wanted to show that, collectively, together, we are a force to be reckoned with.”

On the night of the Opening Day boycott, it wasn’t hard to see echoes of those London protests in the Oakland Coliseum parking lot. In the airspace complicated by the green and gold smoke bombs fans occasionally let off, there was an utterly serious sense of shared purpose, something almost like patriotism or responsibility. It seemed to hold fans in place, as if the parking lot were a kind of second home that they’d all been enlisted to defend. Very few fans peeled off to go inside the park, even as darkness fell and temperatures dropped. Paid attendance at the game that night was 13,522—the lowest Opening Day draw in Oakland history.

Only a week later, on April 4, Fisher affirmed to the press that he’d be moving the A’s to Sacramento after the end of the 2024 season. There’s a reason that relocation hits fans like “a death in the family,” as Billy Crystal famously said of the loss of the Dodgers to Los Angeles. A’s fans had been prompted to mourn the loss of the team several times before, but after the Sacramento news the diagnosis felt terminal. And it prompted no small amount of second-guessing and regret. Had Oakland’s fight been lost?

Johansen doesn’t think so. Oakland may be losing the A’s, but “the narrative’s changed. And fans did that, right?” he said. “Now, if anyone tries to say, ‘Well, [the A’s had to leave] because nobody shows up at the games,’ everyone will tell you, ‘You’re a fucking idiot.’”

He’s right. As recently as last year, opinions on who and what was to blame for the A’s departure were mixed. Many casual observers, swayed by the sad-looking pictures of a nearly empty Coliseum that are still shared on baseball Twitter, the version of the tale, helpfully articulated last summer by Jeremy Aguero, a Las Vegas–based consultant, that posits, “The [A’s] attendance is abysmal now in Oakland. I don’t think there’s any illusion. I don’t think we should sugarcoat that in any shape or form. That’s exactly why the A’s are looking to find a new home.” Now, however, many recognize that the A’s low attendance was “a self-fulfilling prophecy,” as ESPN’s Tim Keown put it last year. Or, as Ken Rosenthal put it, “This idea that those fans are not quality fans and they’re just turning their backs on the team—I would suggest that the team has turned their backs on the fans.” The consensus has shifted. “Everyone knows who they should be rooting for here,” Braun, of Foul Territory, told me. “And they know a lot more about the story than they would if it weren’t for things like Fans Fest, the reverse boycott, etc.”

But while A’s fans may have changed their reputations, they’ve changed more than that. Most sports fans don’t think much about the politics of sports, how the invisible structures that shape the way we experience sports were put in place, for what purpose, and by whom. In turn, possibilities for how our relationship to sports could change—or why perhaps it should—are never seriously considered. Instead, team owners are capitulated to, and the logic that allows team owners and leagues to get their own way over cities and fan bases gets reinforced, one subsidy at a time. In Oakland over the past year—as in Cleveland 29 years ago, and in Europe in 2021—that logic was challenged. Its flaws were exposed. Ideas for how those flaws could be fixed have been entertained. Perhaps this is how real change on any kind of scale ultimately develops, with the local yearning of industrious people who’re full of grit and also really pissed off. And perhaps this, then, will be A’s fans’ true legacy. Anytime owners do something fans don’t like, fans hear that noxious cop-out that sports are “a business.” But if sports are only a business, shouldn’t fans demand that their economic investment come with some kind of equity stake? (Consider what an $855 million investment gets you in other industries.) Should they—or at least the cities that often hand out public money to these teams—not demand some kind of input or a fairer share of revenues and benefits?

More fans may be coming around to the idea that things don’t need to be this way. “This has totally jumped off the page,” Melissa Lockard, who covers the A’s for The Athletic, told me. “I imagine the league, if they’re being reflective, has gotta be worried. This is starting to catch on. Other fans in other markets are starting to see what’s possible if they band together. They’re not going to take it anymore. If I’m a White Sox fan and you’re saying you’re going to leave, I’m calling your bluff. I don’t know how easy that would be for fans to do if it wasn’t for Oakland.”

“It’s really hard to put together movements like this in sports,” Braun told me. “A’s fans have done that. They represent why we dedicate so much of our lives to a sport to begin with.”

Photo by Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

More fights about pro sports teams, publicly funded stadiums, and what teams and fans owe one another are on the horizon. As the sports economist and stadium-subsidy watchdog J.C. Bradbury put it to me recently, “There’s so many stadium deals going on that I can’t keep up with them all.”

The side effects of these efforts will stretch beyond Oakland. In just about every stadium development, owners attempt to get some degree of public funding from their host cities. (One study, coauthored by Bradbury, states that “Between 1970 and 2020, state and local governments devoted $33 billion in public funds to construct major-league sports venues in the United States and Canada, with the median public contribution covering 73 percent of venue construction costs.”) They do this because they’ve come to expect that they should be able to and because socializing the costs of the pro sports business has become integral to its revenue model. As owners try to reinforce that expectation, questions of ownership, equity, and representation will move to the forefront of the fan experience. Why, again, do cities and fans invest so much into pro sports but get so little—in revenue, equity, or assurances—in return? How should fans who are perhaps feeling fed up with the arrangement advocate for something fairer?

And in this sense, Leon and Johansen’s fight, far from having been lost, is only just heating up. That’s certainly how they see it; it’s one reason Last Dive Bar and the 68s are planning additional protests of Fisher and MLB that’ll be taking place throughout the summer. They’re planning one in Sacramento on April 27, when the Las Vegas Aviators, the A’s Triple-A affiliate, come to play the River Cats, who’ll be sharing their stadium with the A’s next year. As Leon put it to me, “The fight continues.”

I tried reminding myself of this the night of the boycott, when I found myself in a funk. It was around the fourth inning, curiosity had gotten the best of me, and I’d turned toward the Coliseum. Illuminated in the dark, this building I’d spent so much time in appeared strange and stark and beautiful. I decided to see for myself how alien and empty it felt inside. I justified it by citing journalistic responsibility. Plus, The Ringer had already paid for a ticket.

The experience left me feeling hollow. Inside it was quiet and sort of eerie and dour—the A’s were already losing big, and the place felt as empty as I’d thought it would. I tried to find a grim satisfaction in this, but there was still a baseball game going on, and the PA system still pumped up the crowd anytime something halfway good happened, and bunting still hung ceremoniously from the bleachers, and the A’s were probably still moving somewhere else after the season. It all reminded me, in the moment, of how large and unstoppable the forces arrayed against A’s fans were. In a borough or a blue-collar town, fans fighting for the future of their team are never just up against Fisher types—individuals with a perverse agenda. They’re up against an industry with resources and federal antitrust exemptions. In the best of circumstances, to succeed, you need amenable and empathetic league commissioners, probably a lot of money, and ideally the support of a culture that vilifies greed and plunder. How much of a chance did A’s fans, living in a city like Oakland, playing in a league as conservative and patriarchal as MLB, ever really have?

Then I walked back outside. I paused at the top of the elevated concrete pathway that loops down the Coliseum’s back entrance to the south lot. I realized as I was standing there that it was the top of the fifth. Ever since the reverse boycott, it had become tradition in Oakland to reserve this half inning for the game’s most vociferous and persistent “Sell the team!” chants. I’d wondered what Leon and Johansen would try to do to honor the tradition, although if I’m being honest, I’d been somewhat skeptical about what protests issued from a parking lot in the dark would look like to the people ensconced in the Coliseum.

What they looked like, from my vantage, was a kind of uprising—undeniable and all its own. Fans had spilled out from the centralized scrum in the lot’s southeast corner and taken to their cars. In the dark, this gave an impression of an altogether different kind of scale. I blinked, and suddenly it seemed as if the entire parking lot were full of fans hanging out of their car windows, honking their horns, slamming open palms on their hoods and car doors, and flashing their high beams. Those fans still on their feet filled the empty spaces and started up the famous chant—“SELL THE TEAM,” “SELL THE TEAM”—and then, catching on, the street bands started playing their instruments in time with the beat. Soon the whole lot was in time, acres’ worth of summoned anger composed of horns, lights, drums, and the vuvuzelas and shredded voices of the pissed-off thousands, Leon and Johansen among them. The expanse was lit up like a switchboard, and the clamor and light ricocheted off the concrete behind and around me. It felt, for a moment, like all of Oakland could have been down there—and like it would have been impossible not to hear them.

Dan Moore is a contributor to The Ringer, Oaklandside magazine, and Baseball Prospectus. Follow him on Twitter @DmoWriter or at www.danmoorewriter.com.